feature / faculty / media-design-practices

October 29, 2019

By: Solvej Schou

Building a more inclusive house: ArtCenter series explores design futures beyond the Bauhaus

Founded as an art school in 1919, Germany’s Bauhaus—meaning “house of construction” or “building house”—is often characterized as emphasizing minimalism, sleek lines, utility, mass production, and architecture and typography in its union of art and design.

Long after the school was closed by the Nazis in 1933, the movement’s impact is still felt, from the design of furniture to iPhones. And yet, longtime narratives around the Bauhaus have excluded diverse perspectives, stories and insight.

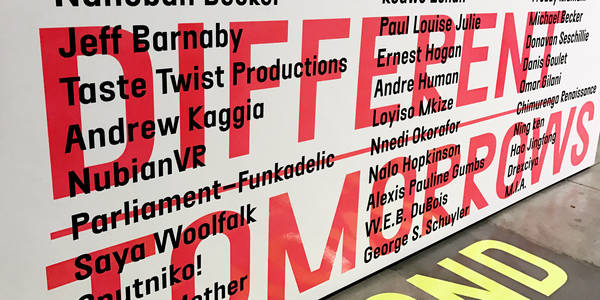

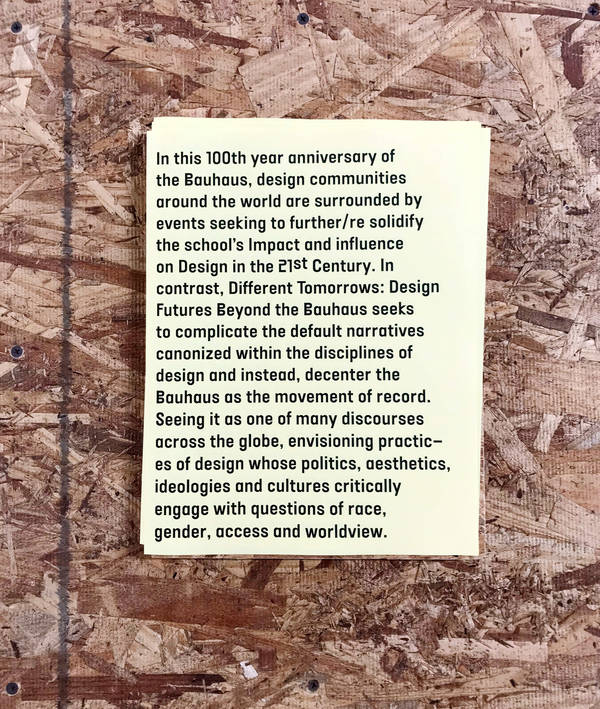

Timed to the movement’s 100th anniversary, ArtCenter’s week-long early October series Different Tomorrows: Design Futures Beyond the Bauhaus—a follow-up to the 2017 series Different Tomorrows: Beyond Whiteness—brought together scholars, artists, activists and designers to challenge the Bauhaus as the movement of record with discussions related to gender, race and global perspectives.

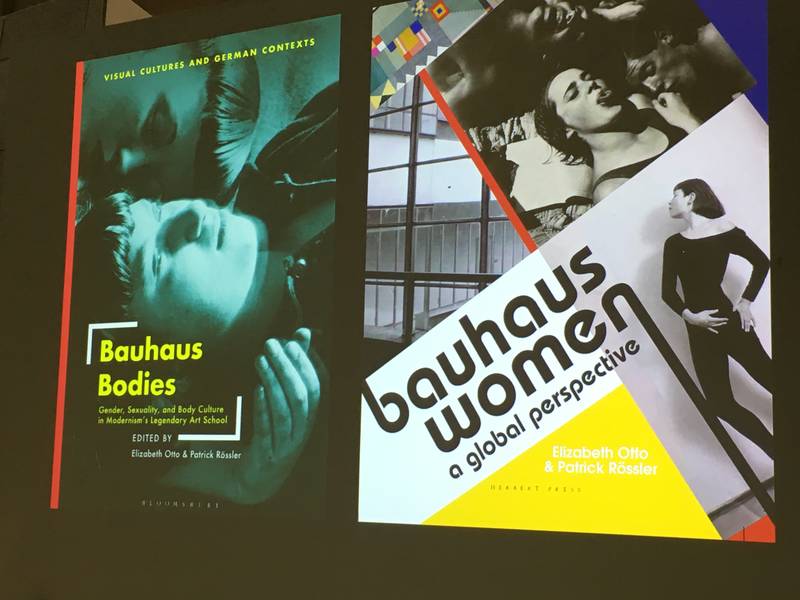

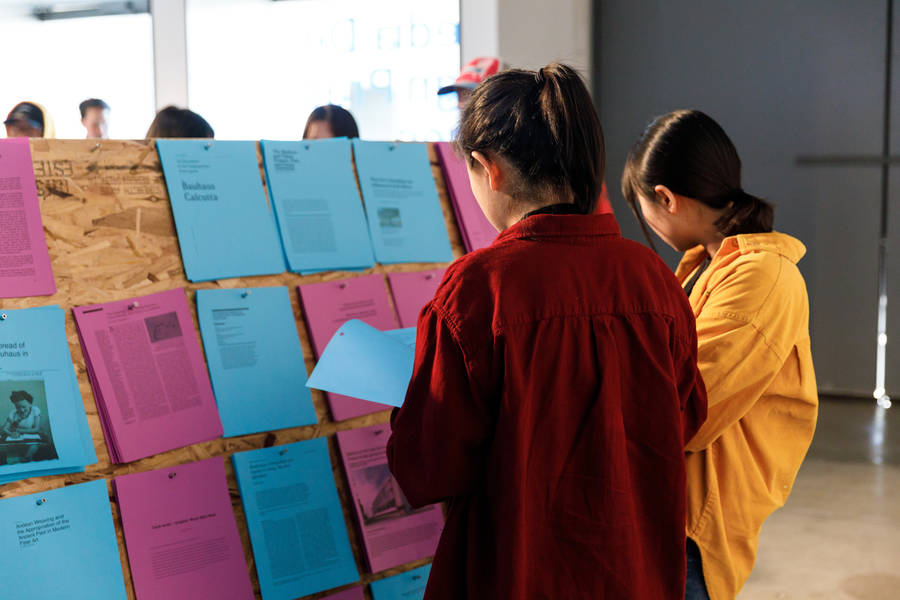

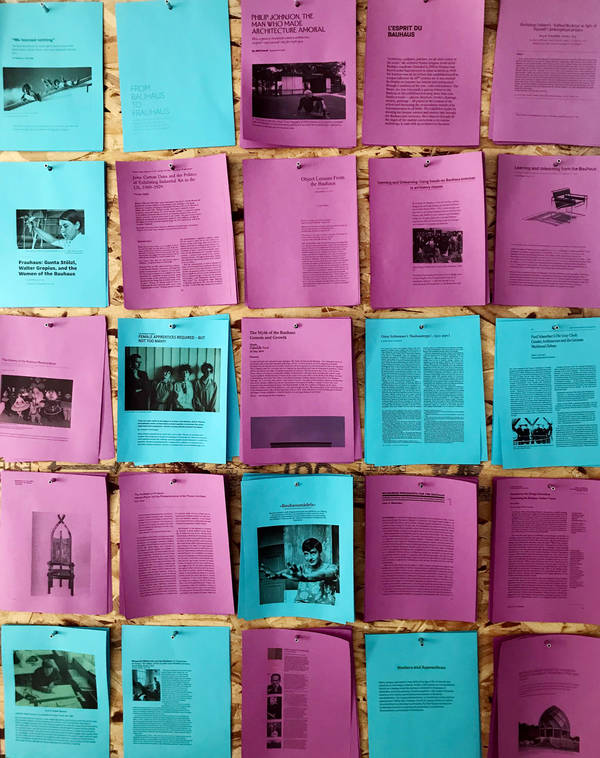

Organized by graduate Media Design Practices (MDP) Department Associate Professor Sean Donahue and Professor Elizabeth Chin, the series included a reading room at the 950 building’s Wind Tunnel Gallery with 100 texts and projects questioning the Bauhaus legacy, and a docent tour of the Getty Center’s Bauhaus archives. A reception and symposium featured University at Buffalo Associate Professor Elizabeth Otto, author of the 2019 book Haunted Bauhaus: Occult Spirituality, Gender Fluidity, Queer Identities and Radical Politics; Leah Hsiao, a lecturer at China’s Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts and a researcher at the Bauhaus Lab in Germany; and Raquel Franklin, head of the Universidad Anáhuac México’s Theory of Architecture Department.

AC: What kind of outcomes did Different Tomorrows: Design Futures Beyond the Bauhaus generate?

Sean Donahue: There are several outcomes for both our immediate ArtCenter community and for the wider community of makers. At the core of all of them is an investment in work that seeks to complicate the default narratives canonized within the disciplines of design, particularly as they relate to issues of race, gender, access and worldview. With this symposium, we wanted to offer, in this 100th year anniversary of the Bauhaus, a dissenting voice to the multitude of events seeking to further and re-solidify the Bauhaus school’s impact and influence on design in the 21st century.

AC: What did the symposium’s speakers bring to Different Tomorrows? And what kinds of works were featured in the in the reading room?

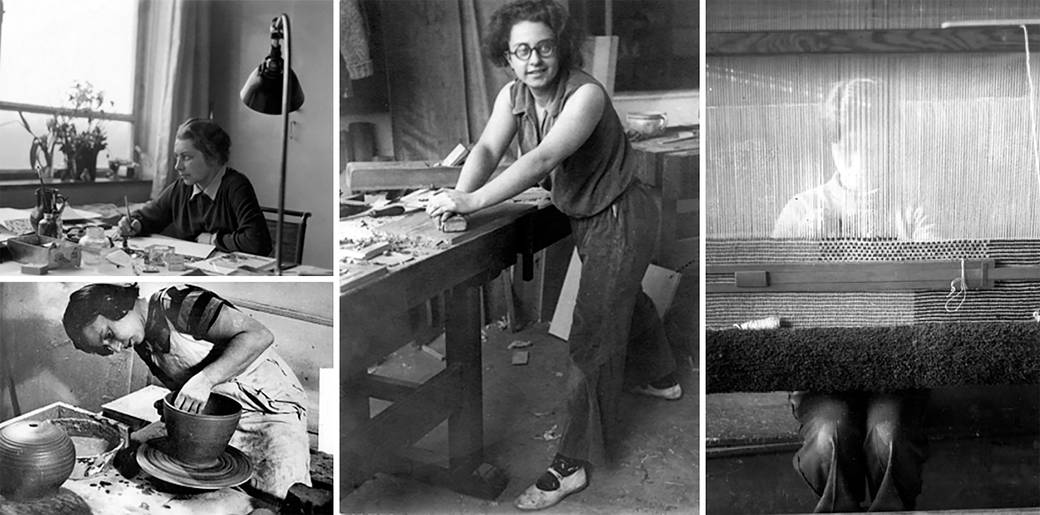

SD: The speakers each contributed to this complication. Leah Hsiao discussed the growing and long relationship between the Bauhaus and China. Elizabeth Otto emphasized the social experimentation that was critical to the Bauhaus endeavor—something vastly under considered in the United States. Raquel Franklin from Mexico City discussed the exhibition proposals created by Bauhaus director Hannes Meyer that offered a decidedly different vision of the Bauhaus than the 1938 MOMA show in the U.S. The images selected for the reading room were chosen to counter the default historical recollection of the Bauhaus as being the domain of five white men. They included voices working at the same time in other parts of the world, as well as photographic testimony that the Bauhaus included women, with individuals like Michiko Yamawaki, Gunta Stölzl, Ruth Hollós-Consemüller, Wera Meyer-Waldeck, Katt Both, Marguerite Friedlaender, Rose Krebs, Louisa Catherine (Kitty) van der Mijll Dekker, Benita Koch-Otte, Alma Siedhoff-Buscher, Otti Berge and Friedl Dicker making, in the studio, and asking material questions. It’s a unique testimonial to the leadership they exercised in the creation of the intellectual and material offerings associated with the Bauhaus school.

Elizabeth Chin: The version of the Bauhaus that was promoted in the U.S., and which has influenced places like ArtCenter, was stripped of many of the concerns that had fueled the development of the Bauhaus. Two of the most important, from our point of view, were the experimental educational model and the school’s concerns for social well-being. The latter was rooted in an understanding of the greater good that was not premised on client-based commercialism. They were, after all, Communists. This leads to a critical understanding of the Bauhaus and its participants not as a monolithic entity as a multifaceted, and often conflicted, institution. It’s important to contextualize the Bauhaus. I’m trained as a political economist, and I’m always interested in the complex interplay of larger systems on specific events or things. My piece “Bauhaus and the People without Design History” [in the just-published Bauhaus Futures by MIT Press] is a tribute to Eric Wolf, the anthropologist who wrote Europe and the People Without History. Inspired by his work, which argued that Europe has always been deeply enmeshed with those it defined as “without history,” my essay looks at classic silver and ebony tea sets to ask, “Where did those materials came from? And under what conditions?” Most materials came from outside of Europe, and were deeply implicated in relationships of colonialism and the global economy. While places like Africa might have been seen as “without design history,” I question whether the design history of the Bauhaus itself could have existed without these relationships, and how we might consider design history itself as more complex as a result.

AC: In what ways did this series differ from the first Different Tomorrows in 2017?

SD: The difference is primarily the moment at which each phase of Different Tomorrow's inquiry directed its lens. Different Tomorrows: Design Futures Beyond Whiteness directed its efforts towards challenging the norms being advanced in the growing areas of design focused on the “Future” as a framework for envisioning new design trajectories. In this Different Tomorrows, we looked at design’s Bauhausian “origin” story as a way to expand design’s narratives.

EC: By bringing a set of questions to consider the Bauhaus, now in its 100th year, we’re probing both into the past and the future. We’re investigating some of the ways in which design has—and could—situate itself in relation to the past, the future and to the Bauhaus itself. Stock narratives leave out so much that is pertinent to understanding how we got to where we are and where we might go in the future. We consistently focus on questions of race, class, gender, sexuality, culture and other forms of so-called difference that get built into design practice and culture as forms of inequality.

AC: What is the importance of the Different Tomorrows series for both the Media Design Practices Department and for ArtCenter as a college?

SD: One of the historical aspirations of a graduate design education is to advance the discipline. An essential part to achieving this is asking critical questions. How do design’s historic foundations reconcile with an eagerness to advance issues of social justice, inclusivity and participation? Interrogating how different foundational narratives are complicit in producing conditions of erasure, consumption and ecological disaster supports a different kind of design contribution: a “Different Tomorrow.” ArtCenter looks to the Bauhaus for so many reference points, from pedagogy to physical architecture—just think of the bridge at the Hillside Campus. The opportunity to discuss ways in which different aspects of the Bauhaus and other reference points across the globe can uniquely support design’s contemporary practice is fundamental. How will design and a design education prepare students whose future will be spent shaping this century’s unique opportunities, conditions and challenges in contexts across the world?

EC: The universalism that characterized the Bauhaus post World War II, and which still remains fundamental to most design discourse, is no longer enough. In that moment after WWII, the terrifying potential for worldwide destruction fueled a push to define and embrace universal human rights. Our moment is quite different. The flaws in the universal approach are many, and have been vigorously challenged by indigenous peoples. The rapid spread of surveillance technology is not upholding human rights, but rather undermining them through the assertion and enforcement of a variety of state and national priorities. We urgently need to question the ways in which design outputs go to work in the world. To do this, designers must be asked to critically question not just the form and function of what they make, but the agendas determining what gets made, who benefits, who is left out, and why.