feature / exhibitions / alumni / faculty

August 16, 2017

Writer: Solvej Schou

Images: Courtesy of Stephen Nowlin

PATH OF TOTALITY: ARTCENTER'S ECLIPSE EXHIBITION SHOWCASES ART AND WONDER

“I want to hire the person who does the publicity for the eclipse,” comedian Steve Martin joked recently in a tweet gone viral. He was referring, of course, to the much-anticipated Great American Eclipse, coming to a sky (potentially) near you on Monday, August 21, 2017.

When that eclipse—the first coast-to-coast total solar eclipse in the United States in 99 years—takes place across a “path of totality,” stretching diagonally from Oregon to South Carolina, the moon will fully block the sun for two minutes and 40 seconds, plunging the Earth’s daylight into twilight. Total eclipse watchers will be able to see the sun’s fiery corona—its outer atmosphere—usually invisible to the naked eye. The sun itself will look like a huge black dot, emitting rippling plumes of plasma.

For experts and newbies alike, the Eclipse exhibition at the Alyce de Roulet Williamson Gallery on the Hillside Campus is a perfect way to explore the wonder of this natural phenomena. Packed with eclipse-inspired art and artifacts, and co-curated by alumnus and Williamson Gallery director and curator Stephen Nowlin (MFA 78 Art), Williams College astronomy professor Jay Pasachoff and Lick Observatory Historical Collections Project director Anthony Misch, Eclipse runs through September 24, 2017. Pasachoff, a renowned astronomer and longtime “eclipse chaser,” says Nowlin, approached him two years ago about doing an exhibit tied to the 2017 eclipse.

Everyone who describes experiencing a solar eclipse talks about the deep sensations they have.

Stephen Nowlin

“Whenever you talk to someone who’s seen a total solar eclipse, they talk about the profound experience of it,” says Nowlin, sitting on a bench in one of the gallery rooms, flanked by NASA video of the Earth, sun and moon projected onto three walls.

“I didn’t want to present a science museum show, but rather something immersive and emotional,” he adds. “The artworks as a group engage with the symbolism of a solar eclipse. You can’t recreate the actual experience, but you can focus on its symbolic meanings and the real evidence-based science of it—not superstition—and how an eclipse can have transcendent qualities.”

Eclipse includes contemporary work by artists Russell Crotty, Stephen Dankner, Rosemarie Fiore, Michael C. McMillen, Jacqueline Woods and Graduate Art faculty Lita Albuquerque, as well as almost 100-year-old oil paintings by late lawyer and artist Howard Russell Butler. Objects and artifacts included in the exhibit came from scientific hubs such as the Lick Observatory, The Huntington Library and the California Institute of Technology.

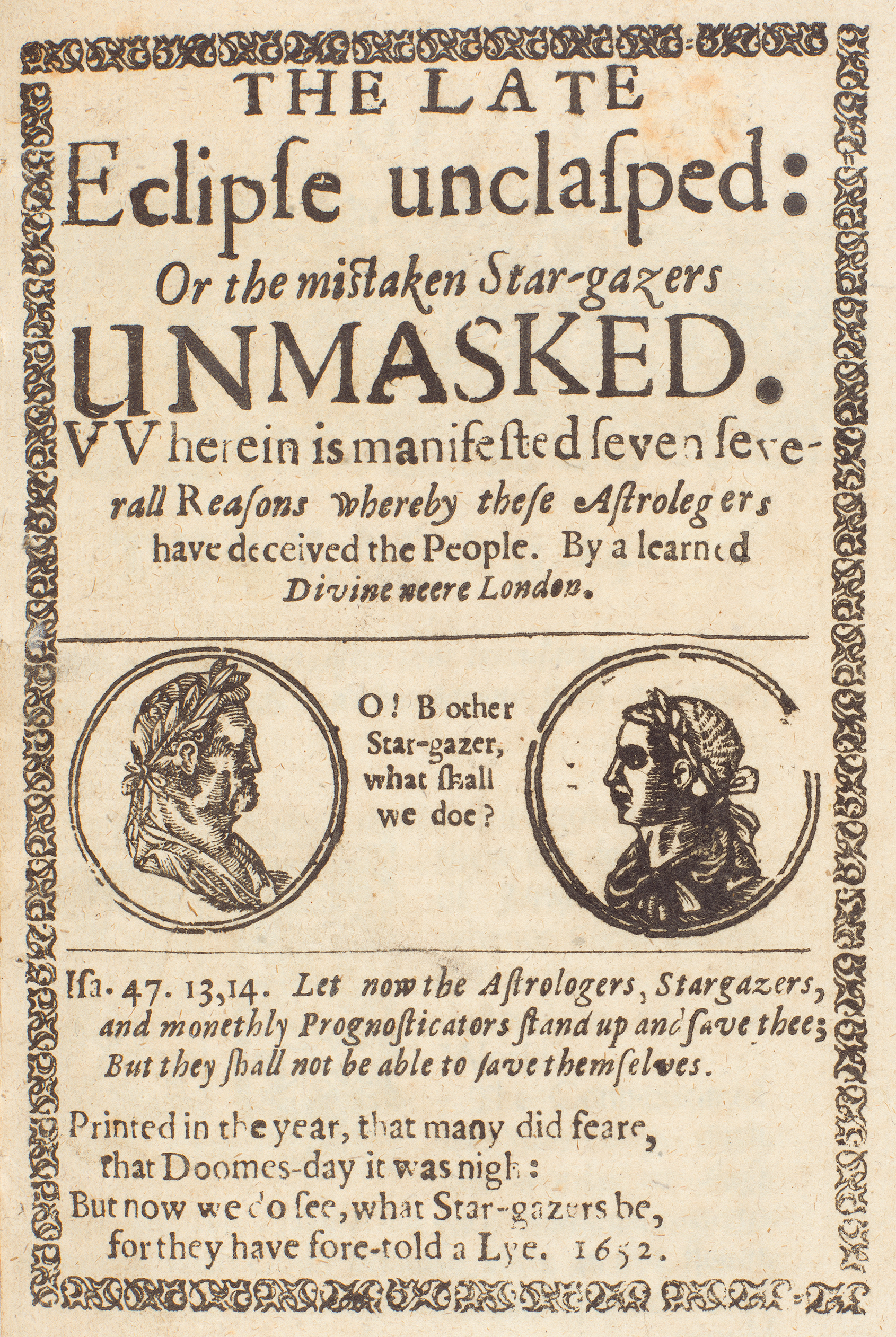

On one side of the gallery, enormous prints of publications and pamphlets from 1652 delve into a solar eclipse that crossed London.

That particular eclipse, before it happened, prompted astrologers to predict three-year apocalyptic consequences and Anglican Church priests to deliver heated sermons. Witnessing occurrences such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and eclipses have united humans throughout history, Nowlin says.

“Whether people knew the sun was a ball of nuclear fission, or whether they thought it was a god, they knew it was the life-giving part of existence,” he says. “When the sun went away, and there wasn’t an explanation, it was a big deal. It’s still a big deal. There’s still a lot of crazy theories and apocalyptic predictions about solar eclipses. I wanted to address that cultural symbolism.”

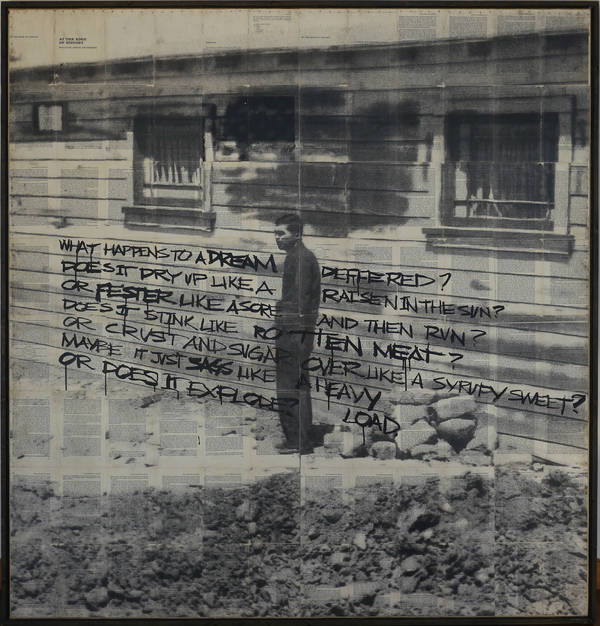

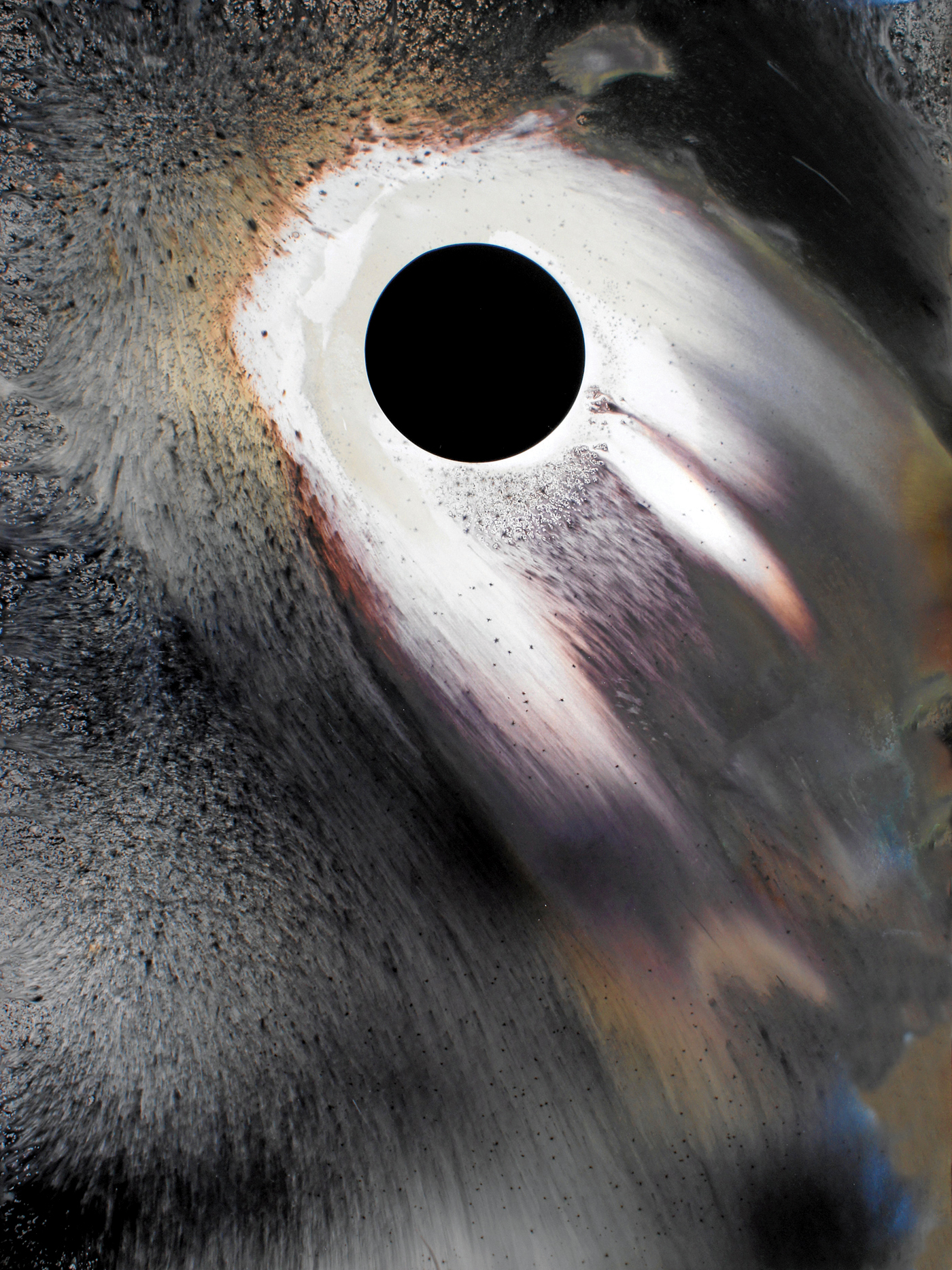

On the other side of the gallery, a floor-to-ceiling wall-to-wall 12-minute video piece that painter, sculptor, and installation and environmental artist Albuquerque created in 2017, titled Eclipse, also addresses the religious symbolism of eclipses, but from a modern perspective.

Text laid out over black and white imagery of water explores the symbolic aspects of Albuquerque’s Catholic upbringing and how they relate to solar eclipses. The piece then powerfully transitions into how the shadow of the moon on the Earth resembles the black pupil of an eye. Swirling colorful footage at the end comes from the 100-inch telescope at Pasadena’s Mount Wilson Observatory.

“Everyone who describes experiencing a solar eclipse talks about the deep sensations they have,” says Nowlin. “An artist—like Lita—takes it further, and attaches it to a narrative. Inside that shadow, when the moon crosses the Earth, every living thing that has eyes looks up. What populates that shadow is a whole lot of living eyes looking out into the universe. It’s wonderful symbolism.”

Butler’s oil paintings of three different eclipses he witnessed in the U.S., starting with one in 1918, feature ethereal and beautifully saturated dark blue skies, wispy brown clouds and the jet-black eclipsed sun smack dab in the middle, surrounded by its bright yellow corona.

Butler would travel to remote areas with his sketch pad to see each eclipse, which would last just two to three minutes. He did some of the first visual representations showing the sun’s solar flares, and parts of the corona, says Nowlin.

“There’s a quaint, charming quality of curiosity and the creative spirit that they [Butler’s paintings] embody that we’ve become calloused to because we can get instant images from spacecraft,” Nowlin notes.

Crotty’s striking 2017 art piece Blue Totality—made out of rectangular fiber glass, plastic and tinted bio-resin pieces in a jagged circular pattern encompassing a black eclipsed sun in ink—has a tactile, physical quality.

The artist, a certified astrological illustrator, is an expert in documenting astronomical events, says Nowlin. Crotty also used to have his own observatory in Malibu.

“His work is very creative, loose and expressive. It always includes a sort of Earth-space duality,” says Nowlin. “The pieces he collaged onto this piece refer to trees, parts of the Earth landscape and the sun.”

Nowlin himself will be camping in Madras, Oregon—along the path of totality, jam-packed with millions of other people—to experience the momentous Great American Eclipse. But if you’re not on that path of totality and only able to view the solar eclipse as a partial eclipse, where can you best view it in your own town?

“You can go up to an unpopulated hillside. Just make sure you watch it with certified eclipse-viewing glasses that are very dark, to protect your eyes,” Nowlin says. “I’m excited to see the eclipse, and know that it will match and exceed my expectations.”