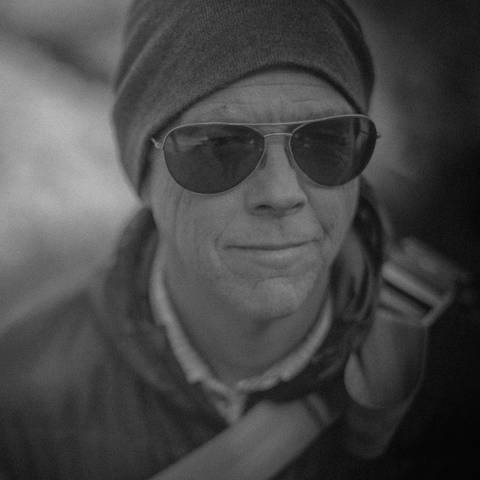

Storyboard: Peter Miller

My strange relationship with structure

I grew up enamored with science. I got my first surfboard when I was nine years old, and let it be known that marine biology became my favorite class in middle school. I was fascinated by the empirical nature of the sciences: the nuts and bolts of it all, the microscopic specifics of how everything in our vast world fits together, or doesn’t.

Of course, that all changed when my grandmother got me my first camera.

At first, I wasn’t totally sure what I was doing. I knew I loved movies, to the point that I would use Tonka trucks and my brother’s toys to re-create action-packed scenes from “Bonnie and Clyde” and “The Wild Bunch.” I also loved music, though the burgeoning punk and hip-hop cultures that I would later find myself enmeshed in had not yet hit the American zeitgeist. I was just a kid with a camera, out in the world, looking for a moment to capture.

In my high school years, in the photos that I found myself most responsive to, I began to seriously examine craft and composition. Suffice it to say, my interest in the sciences—and music too, come to think of it—was dwindling. The one person this did not please was my father. He was a fighter pilot in World War II. To him, a career in the arts seemed frivolous. His ideal path for me would have been to go to Stanford, become a doctor and chase the traditional route to success.

As much as I love my dad, I’m thankful every day that I did not go down that path.

My dad told me I would never get into ArtCenter. He said it was a pipe dream and that my aspirations were unrealistic. To some degree, the simple act of attending ArtCenter was a rebuke to the doubts my father cast on me.

Going to ArtCenter at first was a little like those scenes in war movies where a general tells his platoon, “There’s 120 of you here, and there will only be 60 of you left when all this is over.” Basically, you either hack it or you don’t. Toward the end of my stint there, I sadly began to fall into the latter category. I was burning out. My professors were not happy with me. It was only by the skin of my teeth that I managed to pass most of my classes.

Throughout the course of my life, I’ve had a strange relationship with structure. Even in the work I did in music videos—hanging out with Thom Yorke from Radiohead and shooting music videos for Tupac Shakur, Eazy-E, and Eric B. & Rakim—I found myself drawn toward subcultures (SoCal punk, gangsta rap) that altered the traditional ways of doing things.

What ArtCenter taught me was twofold: it taught me to look for the artistry inherent in these often-maligned genres, which are the two forms of music that give parents the most nightmares; and it taught me that structure and conformity are not the same thing. And I should know—the hardships of ArtCenter almost killed me.

Had my professors not recognized my abilities and guided me to live up to the potential they saw in me, it’s doubtful I would be where I am today. They held my feet to the fire when it came to structure—all so that I would have the skills to make nonconformity pay. To this day, I’m not sure my dad sees me as a structured non-conformist. I know, it’s strange.

Peter Miller

Radical Media

1979 Photography