Color As Revolution: Alum Victor Estrada’s Art Explores Identity, Bigotry, Self, Perception, Memory

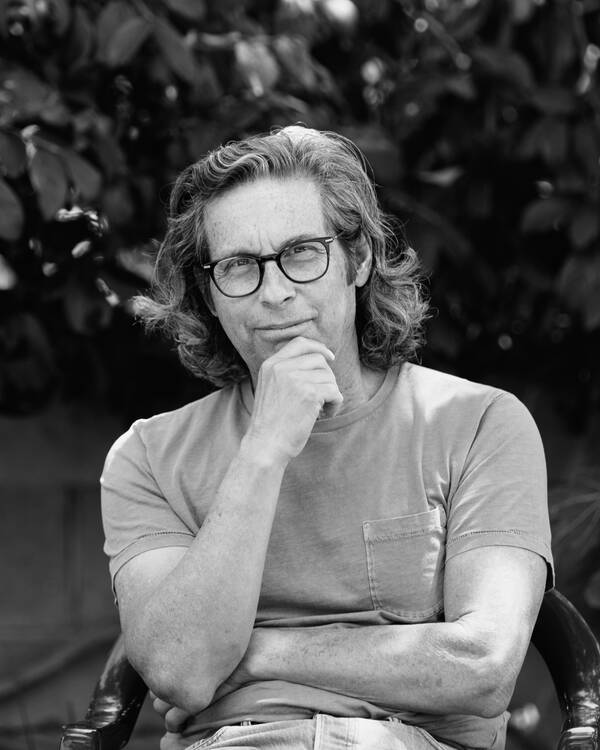

“Racism has existed in this country from the very beginning, and it’s never gone away,” says artist Victor Estrada (BFA 86 Fine Art, MFA 88 Art), communicating via FaceTime surrounded by stacks of art books and in-progress paintings in his home studio in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Northridge.

The San Fernando Valley-raised alumnus, whose decades of dreamlike sculptures and paintings have been in solo exhibitions and group shows in L.A., New York City and Mexico City, dips into and out of the screen. These days, Estrada is preparing for Purple Mexican, an upcoming survey at Cal State LA’s Luckman Fine Arts Complex, which will be centered around his relationship between L.A. and the city of El Paso Texas, where most of his family lives.

There’s a reckoning the U.S. needs to go through, and people of color need to take the reins of discourse.

Victor Estrada(BFA 86 Fine Art, MFA 88 Art)

“Because I don’t ‘look Mexican,’ and I’m light skinned, with hazel eyes, I hear the racist things people say,” says Estrada, as he reflects on COVID-19's disproportionate devastation of Black and Brown communities, and the nationwide protests—sparked by the on-video police killing of George Floyd—against White supremacy, police brutality and anti-Black systemic bigotry. “My uncle was Black and Mexican. He wasn’t allowed to sit with my mother on the bus, growing up. There’s a reckoning the U.S. needs to go through, and people of color need to take the reins of discourse.”

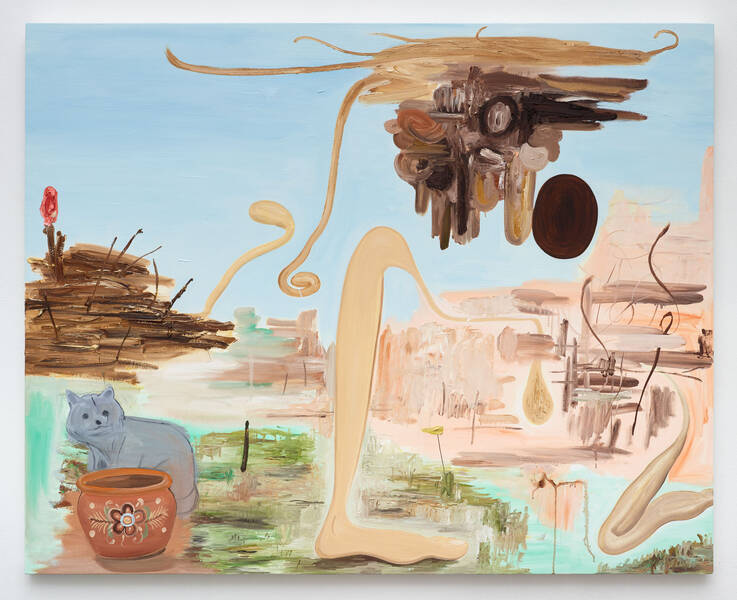

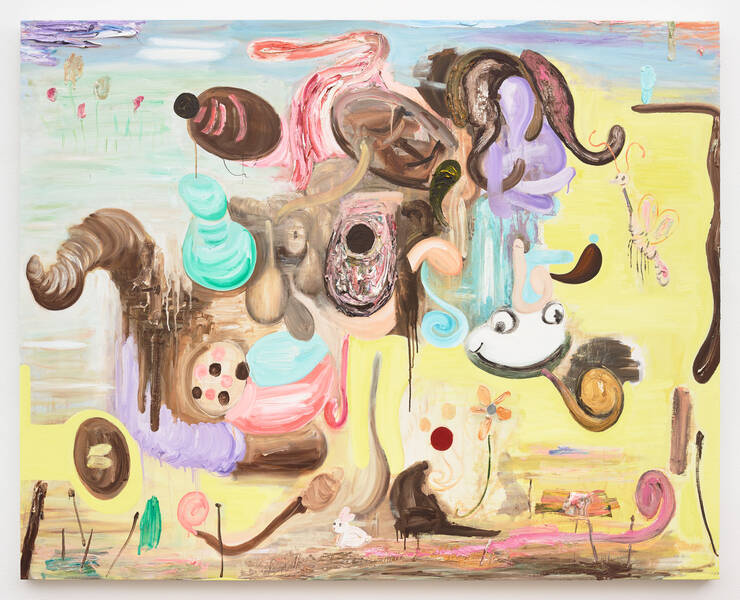

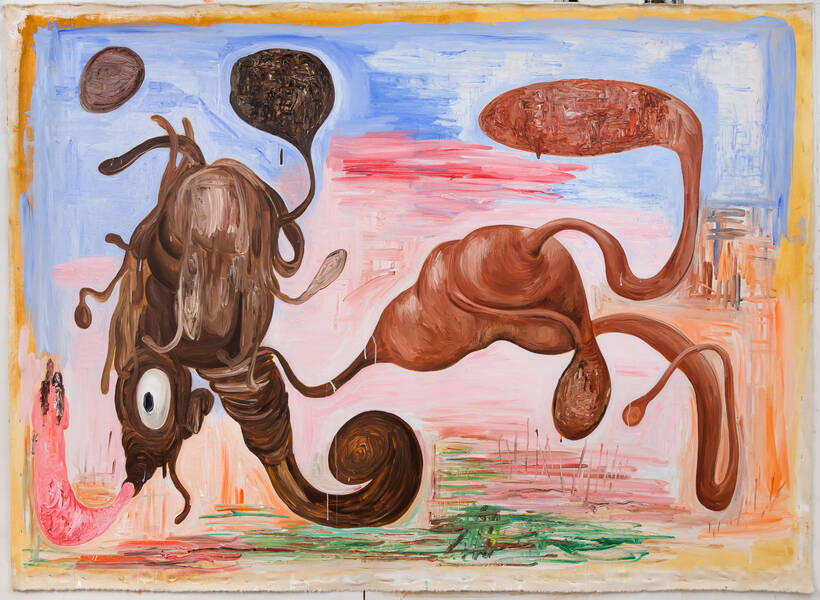

As a longtime artist and teacher—he taught adult public school in East L.A. for 30 years, and he’s been teaching painting at UCLA since 2019—Estrada has done just that. From his 30-foot-long sculpture Baby/Baby in MOCA’s groundbreaking 1992 exhibition Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the 1990s to his newer pieces like his 2018–19 painting Frontera y la Ectoplasmic Electric Sky, his work dives headfirst into that layered realm of self, identity, perception, truth and memory.

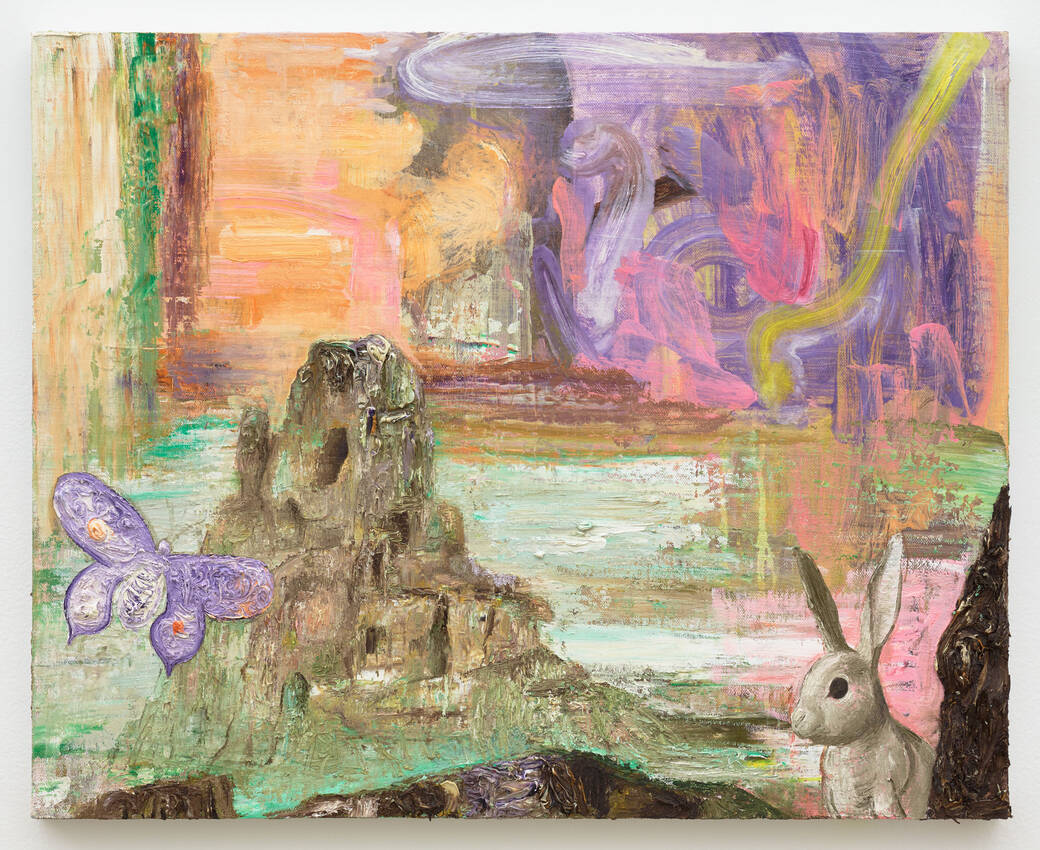

Color in his work—lowrider color, pan dulce color, cartoon color, skin color, flower color—is its own revolutionary force. “Color lies outside the boundaries of language, and it’s the same with art,” says Estrada. “You have to experience it, be overwhelmed by it. What draws me in is the sensorial experience of color embedded in the material, and the form becoming its own thing.”

Estrada’s love of art and color started early. In elementary school, he made paper mâché animals and landscape paintings. As a teen, he drove himself to LACMA to see films. His father, an engineer, was the first person in his family to go to and graduate from college, because of the G.I. bill.

After becoming involved with the student activist group MEChA—founded in the late ‘60s as the Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán—and working as a grounds keeper in Valencia, Estrada studied in El Paso, where he met his wife, before getting his undergraduate and graduate art degrees at ArtCenter. He learned from influential professors like Mike Kelley and Sabina Ott, and alongside classmates Jorge Pardo (BFA 88 Fine Art) and Pae White (MFA 91 Art). “It was a dynamic time to be there,” Estrada says. Philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin’s notion of the “carnivalesque,” of authority being destabilized through humor, also inspired him.

For his 1989 piece For MLK, a bright pink plaster sculpture on wheels, Estrada embedded and gold leafed an imprint from a bust of Martin Luther King Jr., with the gold signifying a heavenly space. “It was a way to conceptualize a new and different kind of social structure, as MLK did,” he says. Estrada’s 1992 museum debut Baby/Baby, with its conjoined giant baby creatures, caught the eye of critics. It expressed his experience both of being a father—grappling with the idea of imposing one’s will—and of having a twin brother. “You don’t know if your kid is going to become an artist or a murderer, and there’s sense of this thing having its own agency,” Estrada says.

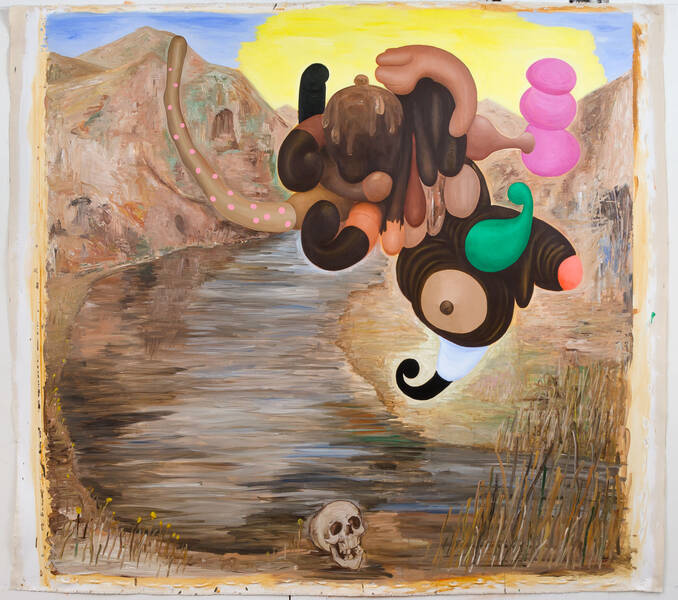

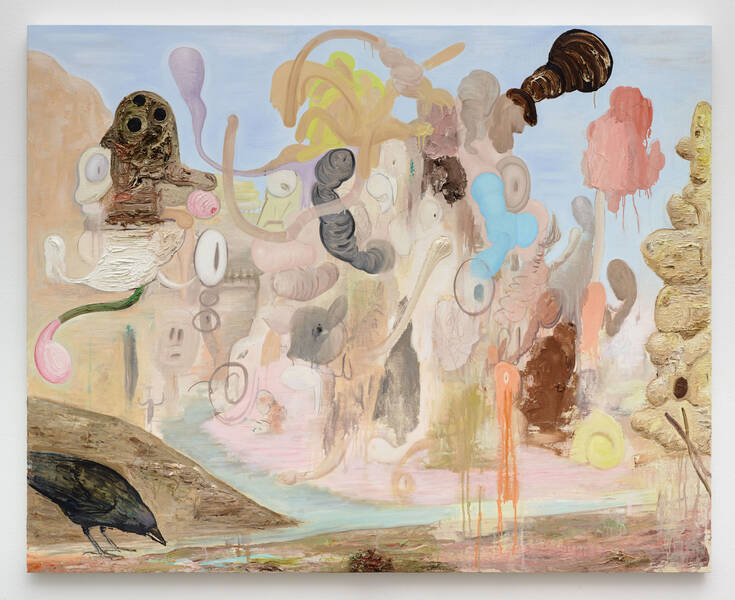

Estrada’s 2013 Figure in an American Landscape, a loose triptych of paintings created for a solo exhibition at New York University, traverses the boundaries of abstract and figurative art. In the series, a dripping, brown mass—based on the Coatlicue sculpture in Mexico City’s National Museum of Anthropology—shifts into a figure floating above a skull. “The series, in part, comes out of me thinking about the U.S. being such a crazy place at that time,” Estrada says. “Today it’s worse. Children are locked up at the border, women are being recolonized by patriarchy, and climate change is barreling down on us.”

He points to some new works in his studio space that will appear in Purple Mexican, whose title comes from a hybrid strain of marijuana from Oaxaca and Pakistan. One in-progress painting features a thick dollop of bright pink paint at its center. Nearby stands a towering 6-foot-tall resin-covered sculpture of foam blocks glued to a metal armature, topped with yellow resin and glitter.

The COVID-19 lockdown prevented him from celebrating his father-in-law’s 90th birthday in El Paso in May. In 2019, he shot video there for his survey. During this trip, he also attended an impromptu memorial in the city a week after a gunman targeted and killed 23 Latinx people at a Walmart.

“The world is a mess,” Estrada says. “In your everyday life, you’re not a group, you’re a person. To me, it’s not about categorizing stuff, it’s about eliminating categories. On some level, I don’t believe in an ideal rightness, that this is how you’re supposed to be.”