CREATIVE RESILIENCE

ALUMNI WHO HAVE SHOWCASED VULNERABILITY AND STRENGTH DURING THE PANDEMIC

ArtCenter alumni have adapted to change during the COVID-19 pandemic in a wide variety of ways. Some turned inward, while others turned outward. They slowed down or sped up. Meet three alumni who embraced their creativity during a time of chaos.

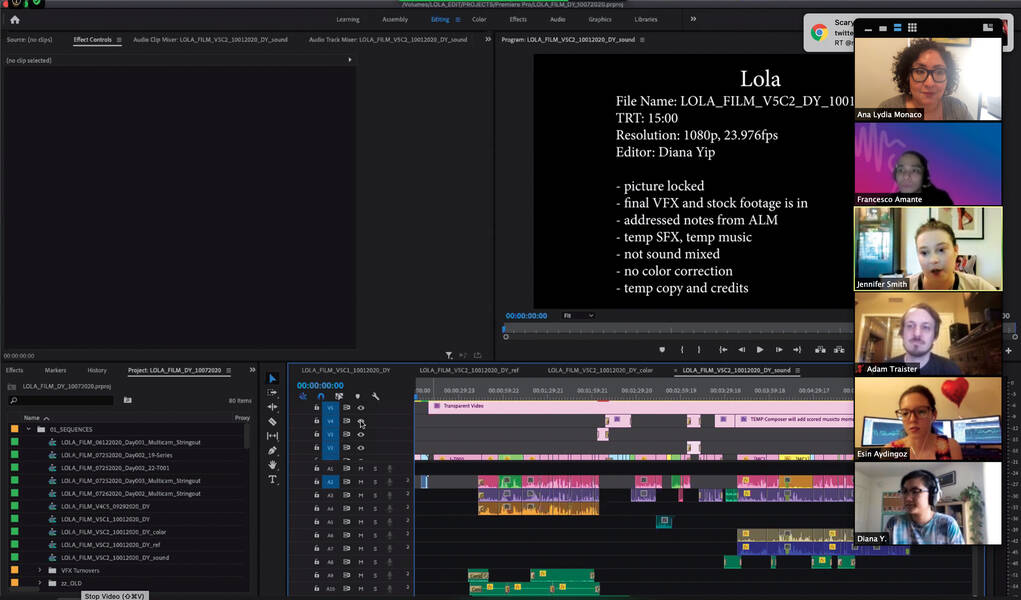

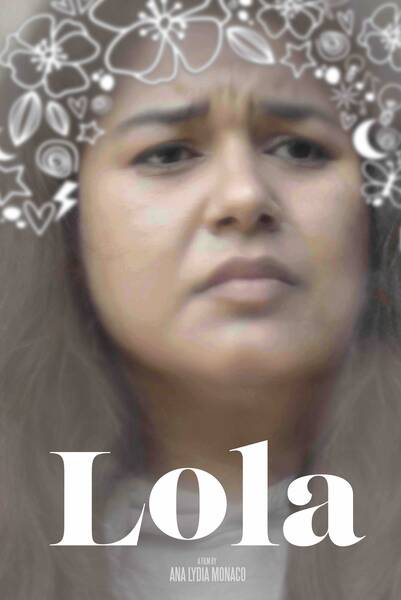

On the first day of filming her short film Lola in July 2020, at a “secret” hiking trail in Los Angeles, Ana Lydia Monaco (BFA 18 Film) was nervous. There were no COVID-19 vaccines then, the virus was surging, and productions had screeched to a halt a few months earlier.

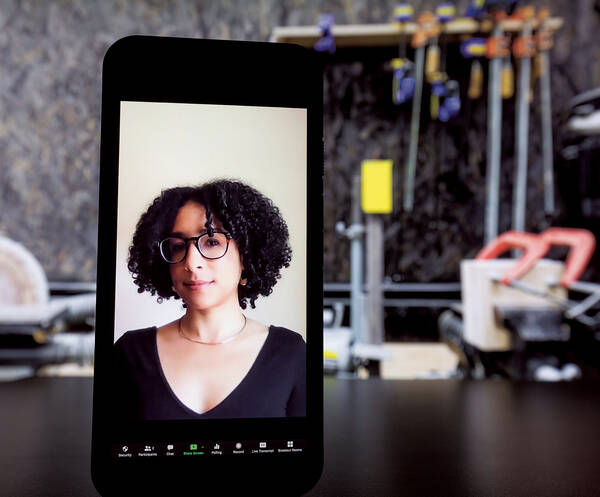

“I felt the weight of the world on me,” says the boisterous writer, director and producer on a spring day in 2021, via Zoom, from the West L.A. apartment she shares with her husband and their Boston terrier, Princess Maya Candice Monaco. “I wanted to film safely because of COVID-19,” she says. “I was also aware that I better make something that’s worth people’s money,” adds Monaco, who raised almost $20,000 through crowdsourcing. “It was stressful.”

Making a film about self-love and self-advocacy, I was very aware of telling people to take care of themselves.

Ana Lydia MonacoWriter, director, producer

In that hiking scene, protagonist Lola (played by Marlene Luna) jogs slowly on a leafy trail behind her best friend Rosalinda (played by Sonia Diaz), then doubles over in pain. Both women wear face masks. Rosalinda dismisses Lola’s concern, tells her to “be healthy,” and they keep hiking. The movie, which Monaco wrote as a student in a 2018 course taught by Graduate Film Associate Professor Joy Kecken, chronicles the journey of Lola, who is plus size, from being blamed by others for her ailing health to advocating for herself after a medical emergency. The short film had its world premiere at the Philadelphia Latino Film Festival, which was held virtually this past June.

“Lola was inspired by my own story, but it was never my story,” says Monaco, who has dealt with having medical issues misdiagnosed because of weight bias. She interviewed 20 women as research for the film. “I make a point to honor each of my characters as a unique individual,” she says. The multiracial Mexican American filmmaker also purposefully cast a plus-size Mexican American woman as Lola. “It was important to me to attract a diverse cast and crew: Latino, Black, Asian, white, gay,” she says.

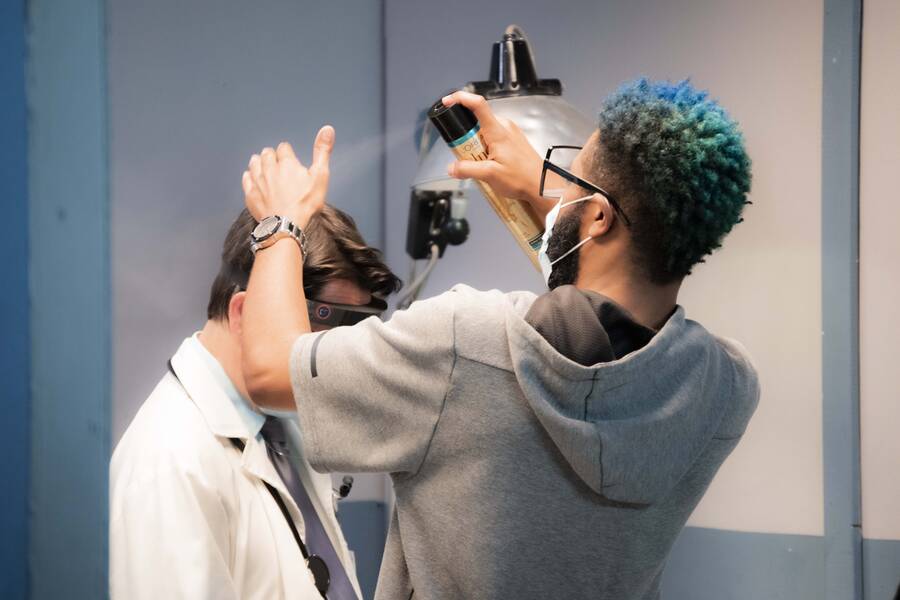

In true pandemic fashion, everyone on set wore face masks and face shields. Actors did their own makeup and wore their own clothes. Monaco hired a COVID-19 officer, who wiped down equipment, handed out hand sanitizer between takes, and made sure everybody on set tested negative for COVID-19 two days prior to filming. Several locations in L.A.’s San Fernando Valley—where Monaco is from and shot the film—fell through because they went out of business.

Monaco had originally intended to finance Lola herself, as she had her other films, including 2018’s Meeting Brown. But when stay-at-home orders were issued in March 2020, Monaco’s development job at a production company went from full-time to part-time to nonexistent.

“I ended up going into a depression,” she says. “I was like, ‘Fuck! Where am I going to get the money for the movie? I don’t have a job.’” She started baking bread, bingeing TV shows, taking walks with her dog, and posting activity to-do lists on social media, including to her followers on Twitter. “Because other people got motivated by the lists, I became more motivated,” she says. She was also prescribed antidepressants, which helped.

A former publicist, Monaco began posting on social media about her pre-pandemic crowdsourcing campaign for Lola, and she soon raised enough money to start filming. While working on the movie, during an emotional time that also included demonstrations for racial justice, the presidential election and the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, she did mental health check-ins with her cast and crew. “Making a film about self-love and self-advocacy, I was very aware of telling people to take care of themselves,” she says.

In 2021, Monaco became a member of Array Crew, director Ava DuVernay’s new database for underrepresented below-the-line crew in Hollywood. She also began producing a TV show for Vice Media and creating branded films for U.S. Bank, while finalizing a TV show pilot script and working on other projects.

“At the beginning of the pandemic I needed a routine, and I also needed to just chill,” says Monaco. “Having time to think and mull over ideas is so important. The No. 1 thing is to be kind to yourself.”

In his office in South Pasadena in the home that he shares with his partner, Kino Wu, Leonardo Santamaria (BFA 17 Illustration) sits in front of a poster by Jena Myung (BFA 16 Graphic Design) that reads “huge clouds. mind: subtle soft” in large white type. He wears a Ruby Ibarra baseball cap with the Tagalog words “Isang Bagsak” embroidered on it. The phrase, as featured in Filipino American rapper Ibarra’s song “US,” means “one fall,” to fall and rise together. “It’s a clap of unity at protests,” Santamaria says via Zoom.

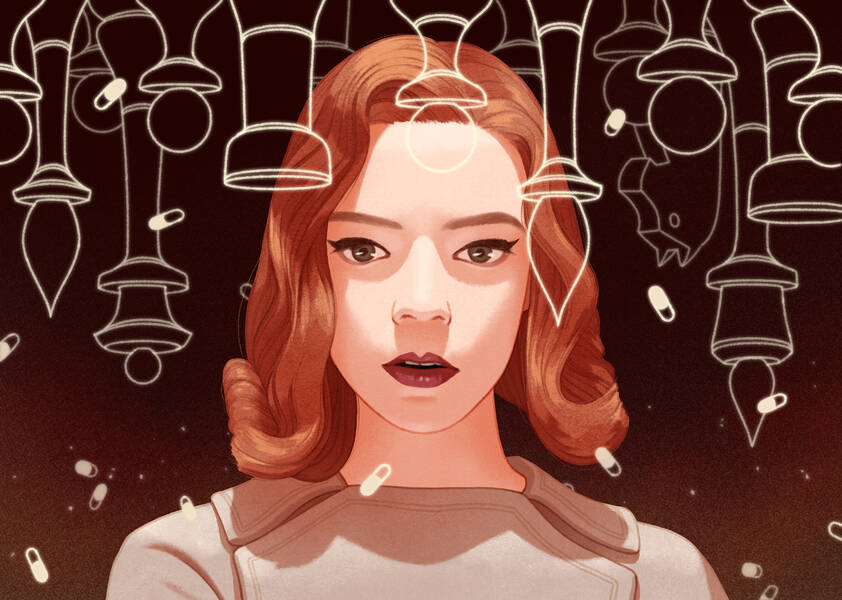

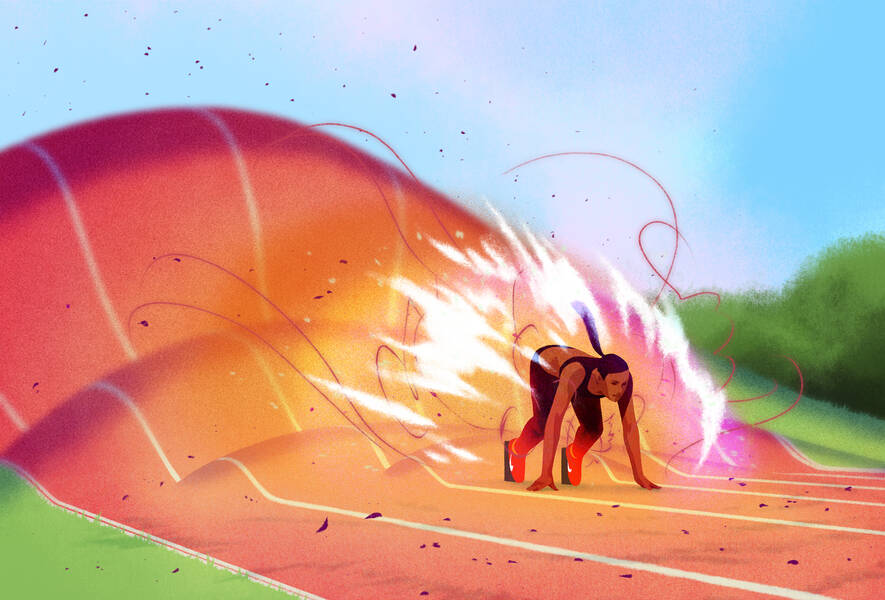

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the award-winning first-generation Filipino American freelance illustrator has created digital illustrations filled with gauzy color and deep emotion for a range of clients, including The New York Times and The New Yorker. His illustrations, and the articles they accompany, address everything from grief to white supremacy.

For the March 2020 New York Times article “Disabled in the Coronavirus Crisis: ‘I Will Not Apologize for My Needs,’” by Ari Ne’eman, Santamaria illustrated the first person story’s exploration of how disabled people are at higher risk of being discriminated against when they’re in need of treatment. In the image, an out-of-focus wall and doorway reveals the profile of a person sitting up in a hospital bed, wearing a ventilator.

“I like doing work about sensitive topics that require empathy,” says Santamaria. “I think, in a way, that it goes back to being an emo teenager growing up in Orange County.”

Santamaria moved to South Pasadena in late November 2020, as COVID-19 cases were rising in L.A. County, after living in Alhambra with three roommates: two ArtCenter alumni and one ArtCenter student. A year earlier, in December 2019, he traveled to China for three weeks with Wu to meet her parents there. When the couple returned, news about the coronavirus was starting to trickle in.

“In the beginning it was hard financially,” says Santamaria. An advertising piece he worked on for The New Yorker, featuring a fiery meteor, was set to be displayed on billboards, and instead became an online video campaign. Assignments dried up. For Santamaria, who has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), listening to podcasts and music helped him concentrate on work amid the stress. He also worked out at home and played video games.

“I'm a social person, but I'm also introverted,” says Santamaria, as his Ragdoll cat, Esme, stretches her legs nearby.

As editorial assignments for Santamaria started to pick up, Wu, who works in visual effects, was impacted when the release date of her first film credit, Fast and Furious 9, was pushed back a year. That delay affected her work visa application. On top of that, Wu’s mother was diagnosed with cancer. With borders shut down due to the pandemic, Wu was unable to travel to China to visit her.

Santamaria ended up detailing their story in a May 2020 interview and illustration for The Washington Post, for a piece about 10 illustrators’ experiences as the U.S. grappled with 100,000 lives lost to COVID-19. During that time, anti-Asian bigotry was on the rise. In his illustration, a figure resembling Wu holds the hand of a figure resembling Santamaria, leading them out of a blue pool of water, lit by a light in front of them.

“She’s leading the way because ultimately there's not much I can do to help except be there for emotional support,” he says. “The light is a metaphor for hope.”

It’s a crisp afternoon, and creative director and designer Elyse Marks (BS 08 Environmental Design) picks up her laptop and takes it to a nearby window to show off the view. Tall trees and the snow-covered Whitefish Range of mountains tower in the distance.

After a decade of working in experiential design for corporate firms in San Francisco and L.A., Marks moved with her husband to the small resort town of Whitefish, Montana (population nearly 9,000) in December 2019. Her sophisticated projects include Salesforce’s 2019 Dreamforce conference, featuring a digital waterfall of analytics, and Mazda’s space at the Detroit International Auto Show. During the pandemic, Marks transitioned to conceptualizing nature-based healing spaces.

“Within the corporate structure, I found that it was difficult to be a woman, a Black woman and introverted, and I never really fit in,” says Marks via Zoom. “The best thing for me was to move from the Bay Area to a smaller and more affordable town with a slower pace of life, and we already had friends in Whitefish. There’s a lot of nature and hiking, which is what I wanted.”

Marks, who grew up in L.A., was just settling into being in Whitefish in early 2020, had started therapy and had begun working remotely on in-person events in Las Vegas and Miami when the pandemic forced the events to be canceled, and she was dropped as a freelancer. “Then all the racial stuff happened,” she says.

After the May 2020 murder of George Floyd, Marks marched in Black Lives Matter rallies in Whitefish. Soon, armed supporters of then-President Donald Trump showed up. “It was scary,” she says. “A Trump supporter came up to a woman named Sami—a biracial woman, like me—and started yelling, maskless, in her face. It became a famous photo in our area.”

Depressed, Marks didn’t work for months. When Sami, who she had befriended, suggested forming an anti-racist support group, Marks, Sami, another woman, and the town rabbi started meeting every week in a park—wearing masks—says Marks, who is half Jewish. The group named itself Ignite, and Marks helped with branding and messaging.

“It was very therapeutic,” says Marks. “It made me realize that even though there are a lot of people scared about change, you still need to live your life and show up in the community.”

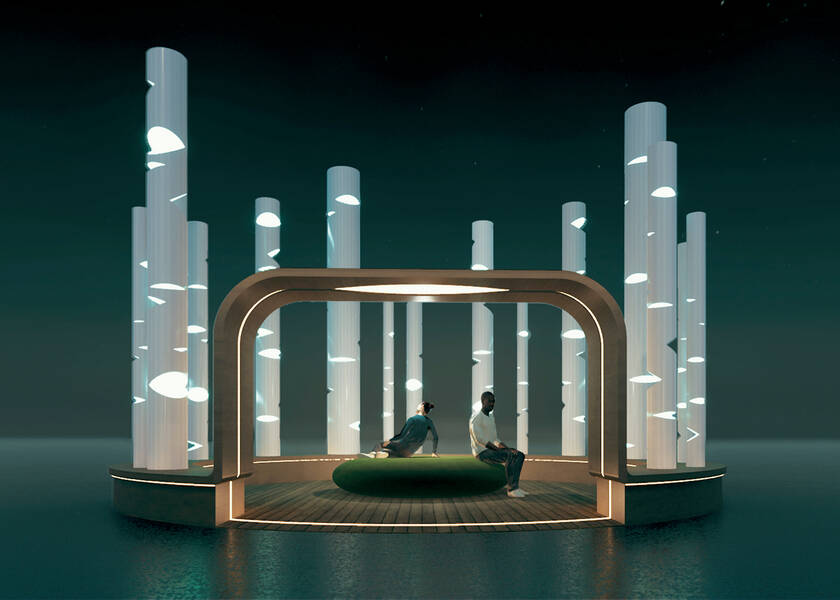

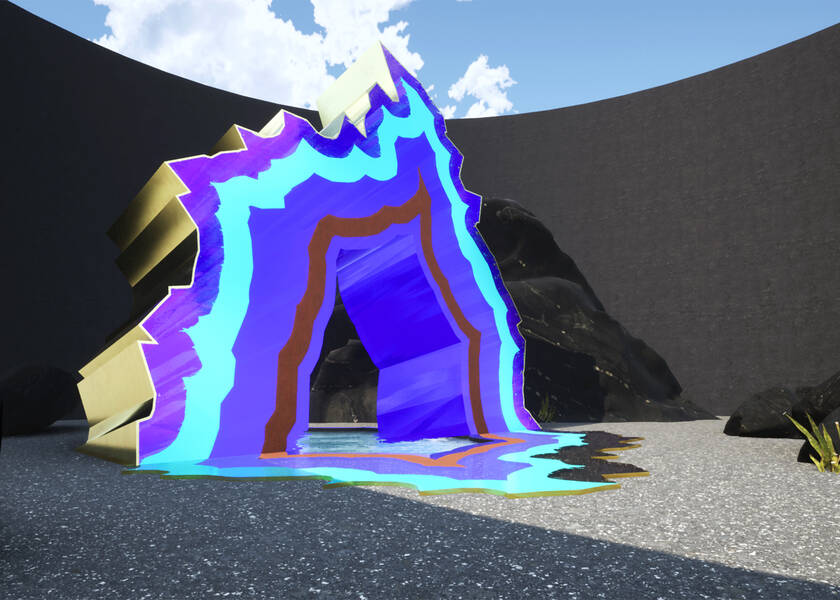

Revived, Marks began conceptualizing meditative spaces such as a circular songbird sanctuary—decorated with wildflowers—that floats over water. Another concept space, shown virtually at Design Miami last December, featured a giant piece of electric blue and purple agate. “Nature is inspiring,” says Marks. “Hearing birds, smelling the air, being in the wild.”

For an art installation last October in partnership with Kalico Art Center in the nearby town of Kalispell, Marks created an immersive landscape at local retailer Nature Baby Outfitter. The installation featured green recycled yarn crisscrossing an empty space outside the store. That project led to Marks serving as an instructor of a community class in person at Kalico—her first time teaching.

“I’ve learned a lot about myself through this pandemic,” Marks says. “Before, my life was just work, work, work. Now, I’m trying to be more vulnerable and reflective, and in touch with myself.”