feature / exhibitions / diversity / staff / college-news

September 13, 2024

By Solvej Schou

Images courtesy of ArtCenter Exhibitions

BIG BOLD DATA: Artists in ArtCenter’s PST ART exhibition Seeing the Unseable: Data, Design, Art

Curators highlight the works of participating artists Mimi Ọnụọha, Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle, and Giorgia Lupi in collaboration with Ehren Shorday

Big data is everywhere, from Apple Watches tracking billions of steps to AI technologies analyzing consumer shopping habits. From the birth of big data and large data sets in the early 1990s to now, artists and designers have found creative ways to interpret what data means.

Part of Getty's PST ART: Art & Science Collide, Southern California’s landmark art initiative, ArtCenter’s exhibition Seeing the Unseeable: Data, Design, Art explores in ways both big and small how contemporary art, design and culture respond to big data’s impact on daily life.

On display from September 19, 2024 to February 15, 2025 at the College’s Alyce de Roulet Williamson Gallery, the exhibition features work from the last 20 years by more than 16 artists and designers, and focuses on concepts about data and data visualization that are loosely organized three categories: Data Humanism, Invisible Data and Data Environments.

The exhibition’s multilayered artists include Giorgia Lupi (in collaboration with Ehren Shorday), Mimi Ọnụọha and Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle—highlighted below by Seeing the Unseeable’s co-curators Julie Joyce, director, ArtCenter Galleries; Stephen Nowlin (MFA 78 Art), artist, curator, and founding director of ArtCenter’s Williamson Gallery; and Christina Valentine (MA 01 Art Criticism and Critical Theory), associate director, ArtCenter Galleries, and curator, ArtCenter Exhibitions.

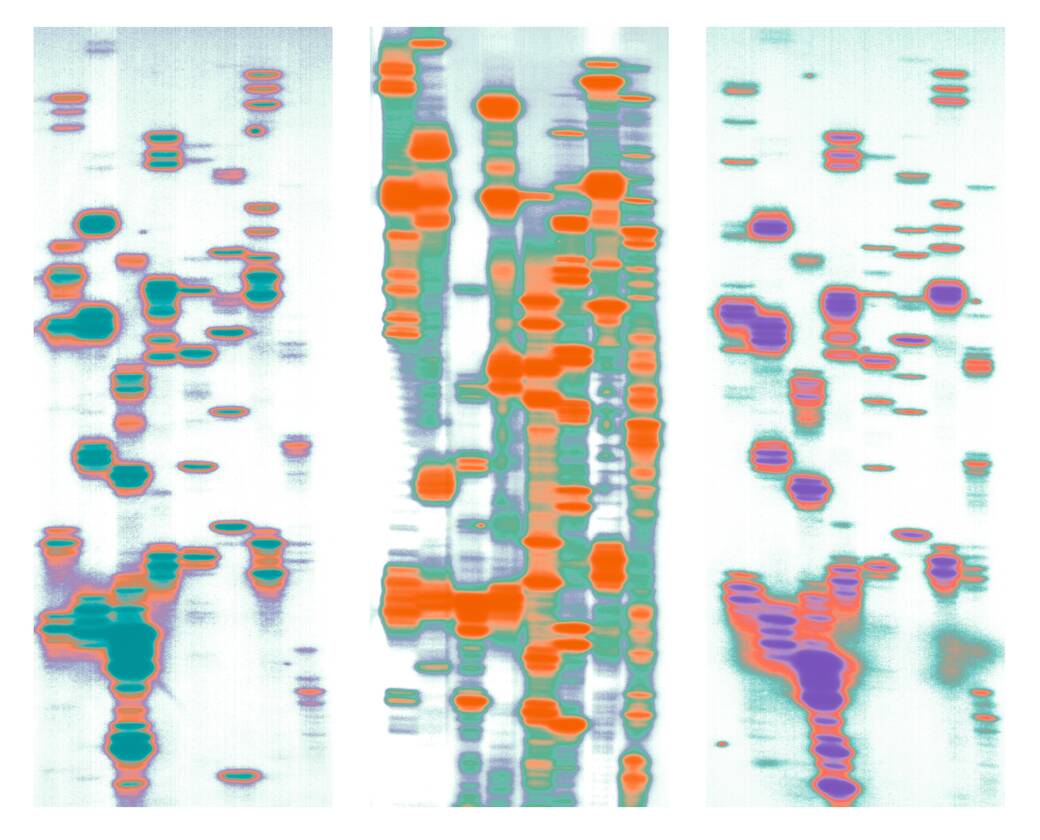

Giorgia Lupi in collaboration with Ehren Shorday

Italian information designer Lupi—a partner at the New York design firm Pentagram, and co-founder of the data-driven design firm Accurat—coined the term Data Humanism, an approach to using data information to affirm humanity, in reaction to computer-generated graphs, pie charts and generic human icons used by mainstream media in the ‘90s.

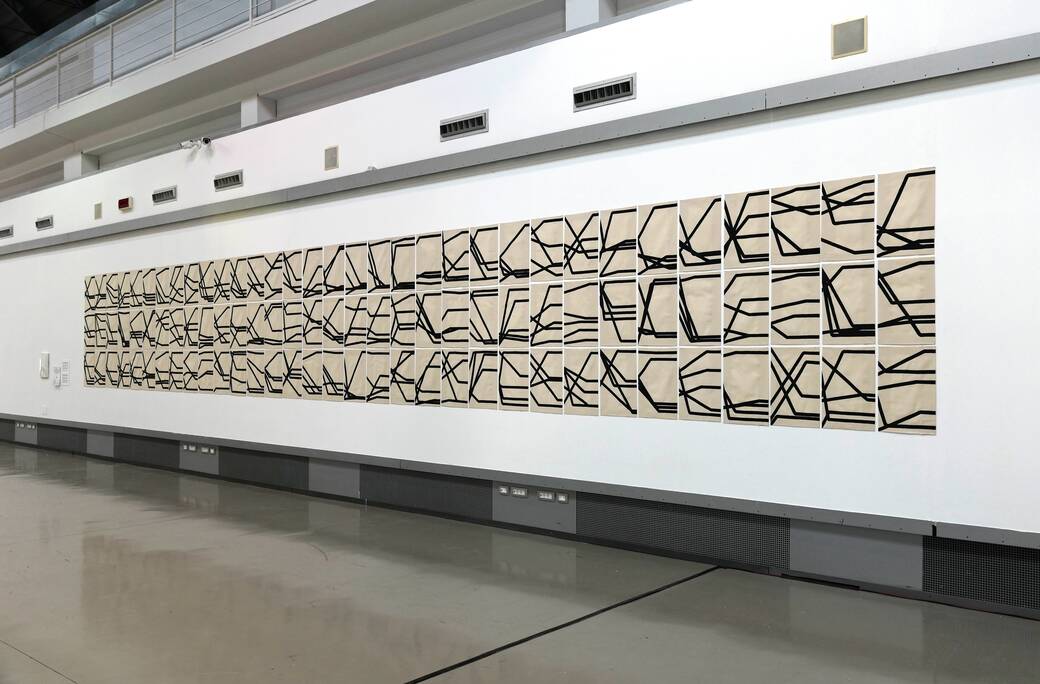

Featured in Seeing the Unseeable as part of the exhibition’s Data Humanism category, her 2022 large-scale installation Incroci, a series of canvas paintings conceived as “data portraits,” created in collaboration with her partner and collaborator, Brooklyn-based artist Shorday, is an exploration of human connections through data.

For Incroci, Lupi and Shorday created a data set—conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic—by asking strangers, and their social media circles, to share five dates (day, month, year) that they saw as significant life moments, from the day of their birth to the present, in 2022. Each canvas painting features rising and falling black lines, signifying a marker of an individual’s important moments, and the entire series—installed in a grid—represents a network of intersected lines as overlapping days among strangers and friends.

“Giorgia Lupi is someone we realized early on would be an essential part of the exhibition,” says co-curator Joyce. “Recognizing our current oversaturation with data, her work emphasizes that it’s important to consider human factors represented by numbers and images. Incroci, representing personally significant information, calls to mind the digital, but is hand-rendered with paint onto raw canvas, like conventional painting. This work uses a minimal aesthetic to represent subject matter charged with emotional significance.”

Mimi Ọnụọha

The exhibition’s Invisible Data category, which references the unseen nature of data and the influence of data biases, features two works by Nigerian American artist Ọnụọha: 2016’s The Library of Missing Data Sets and 2019’s In Absentia.

With recent solo shows in New York and Ontario, Canada, and in group exhibitions at museums including the Whitney Museum of American Art, Ọnụọha places the Black body in relation to technology and focuses on the impact of hidden, repressed and blurred information on society. A Creative Capitol and Fulbright–National Geographic grantee, and co-founder of A People’s Guide to Tech—an artist-led organization that creates guides and workshops on emerging technology—she highlights, in her work, overlooked and marginalized communities.

The Library of Missing Data Sets features three filing cabinets filled with empty file folders, with each folder titled with labels and subjects such as “Cause of June 2015 Black church fires.” These subjects examine the implications of data collection, says Seeing the Unseeable co-curator Valentine. They bring awareness to the ramifications of suppressed and purposefully untracked information.

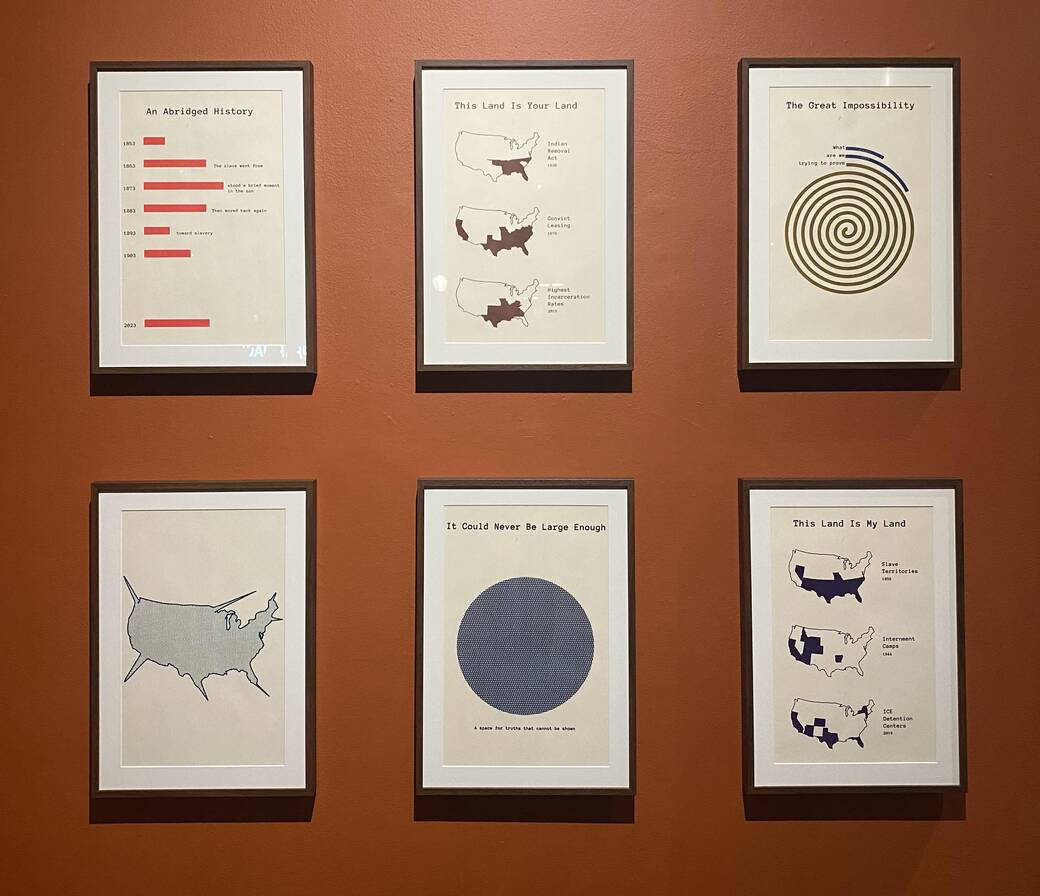

In Absentia showcases six risograph prints in the 20th century graphic style of influential Black sociologist and NAACP co-founder W.E.B. Du Bois. Du Bois was asked by the U.S. government to conduct research on Black rural life in Alabama, and his report with text, charts and tables of data was never published. As Ọnụọha notes on her website, In Absentia begins from this absence and “asks what happens when data is made to disappear by those who seek to obscure the intertwined workings of racism and power.”

“Mimi Ọnụọha’s practice is part of a growing body of work by artists who are critically and thoughtfully reframing the conversation on technology,” says Valentine. “The works we selected are deliberately analog, but reference early iterations of data visualization, as with In Absentia, or evoke the institutional framework of gathering data. The Library of Missing Data Sets reveals the limitations of data mining, the strategy of hidden data as protection or bias, and challenge the idea of gathering information in a totalizing fashion.”

Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle

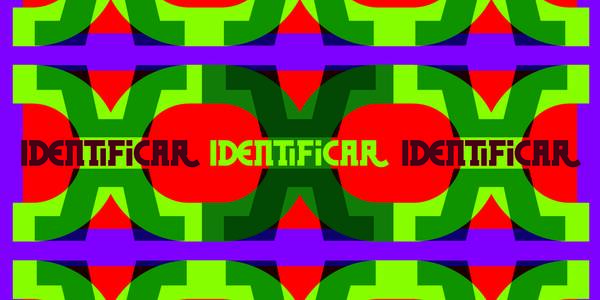

Works in the exhibition’s Data Environments category express concern for Earth’s current state and climate. Included in this section are Spanish-born American artist Manglano-Ovalle’s 2006 works Storm Prototype: Cloud Prototype No. 2 and Cloud Prototype No. 4, and his 1998 work Lu, Jack and Carrie (from the Garden of Delights).

Known for his sculptures, photography and video pieces formed over years of research, and achieved in collaboration with scientific experts, Manglano-Ovalle’s work examines ecosystems, natural and man-made systems, ethical challenges presented by modern technologies, and inequalities related to race, ethnicity and class.

Lu, Jack and Carrie (from the Garden of Delights) combines three colorful digital prints that are images of DNA samples used in genomic mapping. The Garden of Delights, the series the piece is from, features DNA samples from 48 participants. Manglano-Ovalle chose 16 individuals, who each invited two other people to form a series of triptychs that include Lu, Jack and Carrie. Inspired by late 18th century Spanish casta paintings that illustrate hierarchy based on race and class, the series also draws its title from Hieronymus Bosch’s famous triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights.

Storm Prototype: Cloud Prototype No. 2 and Cloud Prototype No. 4 are large-scale cloud-like sculptures made of fiberglass and titanium alloy foil and formed by the study of weather systems and compilations of numerical data from thunderclouds. The works are aesthetic objects that resonate with what science tells us about Earth’s changing climate, says co-curator Nowlin.

“Just as the working principles of science demand that knowledge is formed as an outcome of following evidence, Iñigo Manglano Ovalle's Storm Prototype is sculpture formed as an outcome of following data,” says Nowlin. “His work becomes a metaphor for how science can generate not only information, but also sublime transformative sensations. The aesthetic that blossoms from his process is as much of science and of nature as it is of art.”